How I became an investor

Two months after graduating from the University of Rochester, I moved to Shenzhen, China. This decision was unusual in so far as I knew almost nothing about Chinese culture or history and had never studied Chinese. Moving to and working in a new country as an adult when you neither speak the local language nor understand the culture is a real challenge.

I moved there with a group of roughly 120 Americans, Brits, and Canadians. Expats often cope with the challenges of life in China in two ways: by “banding together” or “going native.” I observed that the vast majority of these folks adapted to the challenges of Chinese life (illiteracy, inability to communicate, cultural complexity, etc.) by banding together. Banding together meant hanging out in Western restaurants and bars to avoid the isolation and confusion that you’ll feel dining at a Chinese restaurant alone or with Chinese colleagues who cannot speak English. While I occasionally spent time with other expats, I largely chose to go native.

Life as an expat trying to assimilate into Chinese society is a process of continuous failure and learning. Ordering food begins with pointing randomly at a menu and hoping for a favorable outcome. After several weeks of disappointment, you'll finally ask to take the menu home, study the words and come back with a strategy to try to mitigate disappointment. This process was further complicated by the fact that at the time I didn't own a smartphone. Remember, this process doesn’t just apply to ordering food at a restaurant, but rather almost every aspect of your life.

After the first eight to nine months of confusion, study, further confusion and further study, I achieved basic understanding on a variety of subjects that enriched my life. I liked that I could ask people about their businesses, ask them if they needed help or give people directions if they were lost all in Chinese. I began feeling like I was contributing to society. I renewed my teaching contract to stay another year. There was still so much I didn’t understand and so many opportunities to learn that the decision was a no-brainer.

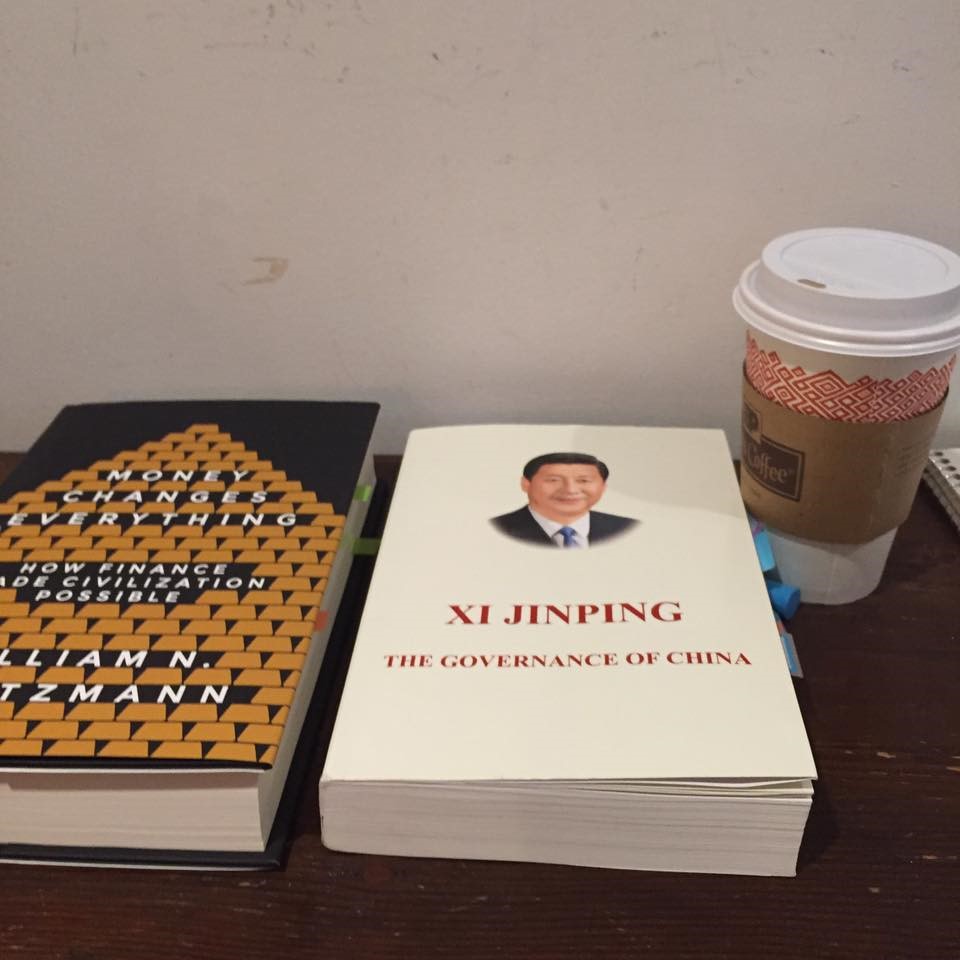

While I enjoyed both teaching grade 2, grade 5 and grade 6 students English and running my small education consulting practice, I knew that neither business was my passion. I was introduced at a young age to economic concepts by my father, who worked as a currency trader for nearly two decades at several large banks. I still remember him explaining the mechanics of a carry trade to me while I was in middle school. I was an avid student of economics and philosophy and finished degrees in both subjects at Rochester. While an undergraduate, I explored the intersection of law and economics and took several courses in commercial law, constitutional law, criminal procedure and law and economics. Given my interest in law, I researched the market structure for legal services in the US.

I did some market research to better understand supply and demand dynamics for lawyers. After a few days of research, I began to suspect that there was a bubble in the market for lawyers (too much supply of lawyers and not enough demand) in the US such that I expected the marginal product of labor (wage) to fall. The market in the US was further complicated by the presence of internet based services like LegalZoom which made whole sub-specialties of law unprofitable.

Thinking more about my comparative advantages I realized that perhaps I’d be best suited to practice law in Hong Kong. Hong Kong is a common-law jurisdiction, meaning the legal system is based on English case law. The system is quite like the legal system in the other former British colonies as well as the US and is highly respected for being fair and efficient. Given that I’d be one of the few non-Chinese lawyers in a region where foreign firms were looking to expand, I thought my ethnicity and language ability might be comparative advantages. I applied to law school in Hong Kong and was admitted to the Chinese University of Hong Kong (“CUHK”) Juris Doctor (J.D.) program. I was thrilled. But my family was not.

After much discussion with my family, I realized that I loved them too much to choose a career that would permanently position me on the far side of the world. My desire for a connection with family wasn’t the only reason for choosing to pass on law school. I realized that lawyers were more of a conduit for facilitating and advising business transactions rather than those that were making the determination to transact (the part of doing business that I found most fascinating). Moreover, after additional research on the practice of law, I became more certain that the practice of being a lawyer is nothing like the experience of studying law academically. After careful consideration of the trade-offs, I decided to pass on law school.

Once I passed on law school, I returned to the US. What to learn next? I researched my options again focusing on my comparative advantages. I was interested broadly in the applications of microeconomics and knew a bit about running a business and wanted to apply those skills to investing. There is no obvious way for former English teachers in China to go into investing in the US, so I needed to think creatively. I reached out to the people I knew in the field and asked anyone I could for a job, even offering to work for free. Finally, I got a break and found a job on a multi-family office investment team doing analyst-grunt work. My favorite part of the job was my supervisor, an analyst around my age who encouraged me to learn by reading the annual and quarterly letters of the 20th centuries' great investors.

At the same time, I was searching for a spot on an investment team, I also considered becoming an economist. Several of my economics professors at Rochester encouraged me to consider becoming a professor of economics, but I had much self-doubt. I’ve never been the strongest math student because I have some skill gaps in algebra and calculus. None the less, I applied to do my Ph.D. in economics at George Mason University (“GMU”). GMU’s department has a strong capitalistic spirit and an awesome group of senior and junior faculty including, Tyler Cowen, Bryan Caplan, Russ Roberts, Peter Leeson, Robin Hanson and James Buchanan. Having spent two years in Shenzhen, the first and largest special economic zone in China, I had an intuition that the field of economic development ought to focus on special economic zones. The opportunity to study development economics as it pertained to special economic zones with someone like Tyler Cowen sounded so cool! Much to my surprise in early 2013, I was admitted to the Ph.D. program in economics at GMU. There was only one problem, I loved investing and didn’t want to stop.

As it turned out, I liked investing much more than I originally anticipated. So many of the concepts I came across from arbitrage to venture capital were fascinating to me. It became apparent to me how many of my passions could, over time, be honed to become competitive advantages at investing. Investing requires abstract reasoning, a love of reading, general curiosity, patience and the wiliness to act differently than your peers. After about five years in the investment business, I now have a much better sense of how little I know about what I thought I understood. My objective over the next 50 years of my investment career is to reduce my ignorance through study, trial, and error.