Target Date Funds Ignore the Most Important Asset You Own

Target date retirement funds are marketed as sophisticated, set it and forget it solutions. Pick the year closest to your retirement, and the fund automatically adjusts risk over time. For many people, this is better than doing nothing. But from an economic perspective, target date funds have a fundamental flaw that is rarely discussed. They ignore the most important asset most people have: their income.

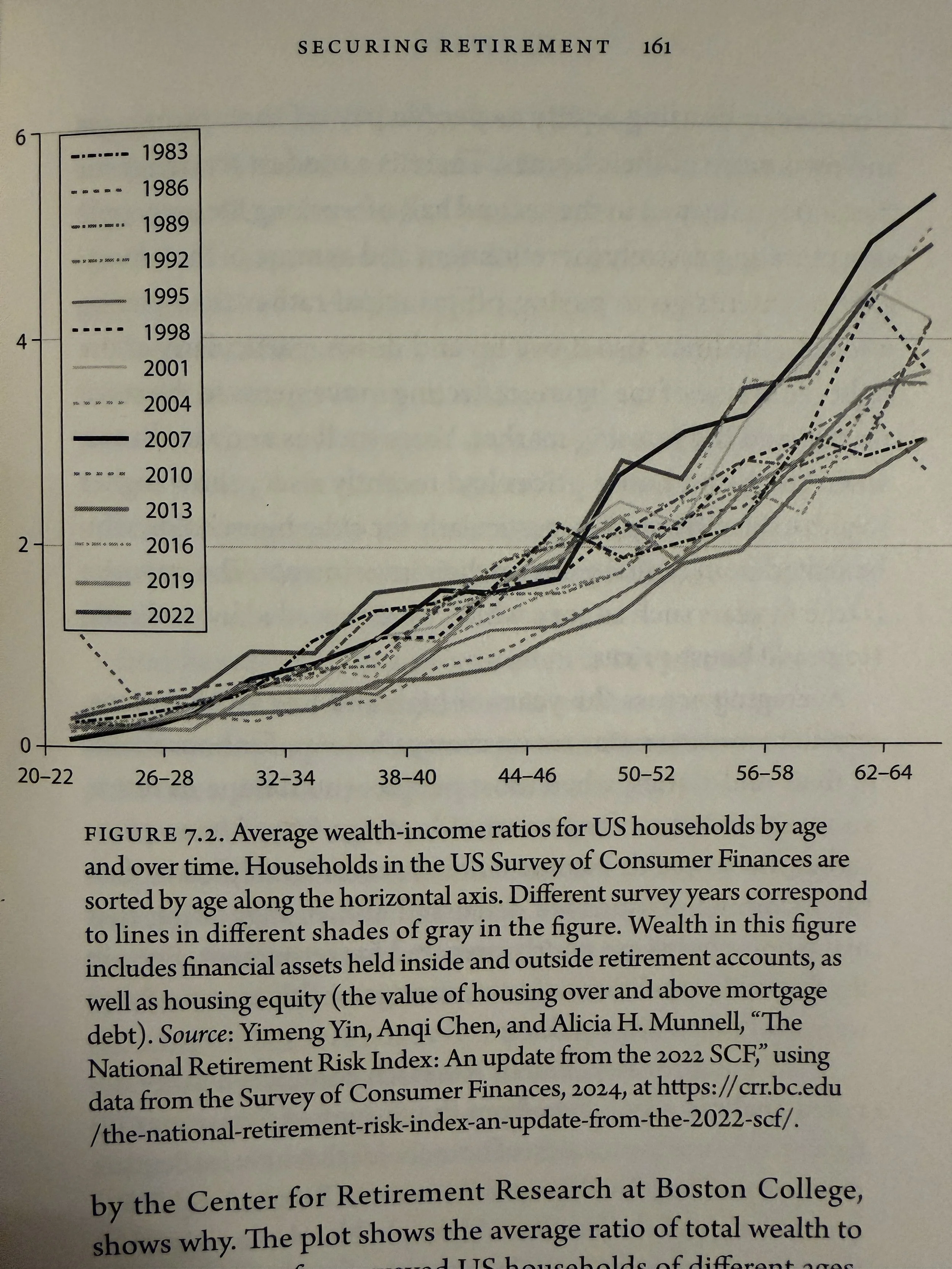

The core assumption behind target date funds is that age determines risk capacity. The younger you are, the more equity risk you can take. As you age, you should gradually de risk. That logic sounds reasonable, but it rests on a false premise. Age is only a rough proxy for risk capacity. What actually matters is your total balance sheet, especially the size (see image below for long term averages), volatility, and market correlation of your human capital.

Consider two people who are both 35 years old. One is a government employee with stable, inflation linked income that has little connection to capital markets. The other works in finance, real estate, or tech, where income, bonuses, and job security are tightly tied to equity markets and asset prices. From an economic standpoint, these two people should not hold the same retirement portfolio. Yet a target date fund treats them as identical.

If your income is already equity like, holding an extremely equity heavy retirement portfolio is often just doubling down on the same risk factor. You are implicitly long equities through your labor income whether you like it or not. In contrast, someone with bond like income can rationally hold far more equity risk than target date funds typically recommend.

Expense volatility matters just as much. A household with flexible spending can tolerate much larger portfolio swings than one with rigid obligations like mortgages, tuition, or dependent care. Target date funds do not model this at all.

There is also a geographic blind spot. Many target date funds embed significant home country bias. But if you earn your income in the U.S., your future earnings, housing exposure, taxes, and political risk are already heavily U.S. weighted. From a hedging perspective, it often makes sense for your financial portfolio to be more globally diversified than the default allocation, not less. The same logic applies even more strongly in smaller economies like Japan or Canada.

Another underappreciated issue emerges later in life. Target date funds collapse everything into a single vehicle. When you eventually want to rebalance or draw down assets, you lose control. You cannot selectively trim U.S. equities that have surged while leaving Europe or emerging markets untouched. You are forced to accept whatever internal reallocations the index provider decides to make.

A more robust structure is to hold multiple regional equity funds alongside fixed income. U.S., Europe, Australia, Asia, emerging markets. This gives you the ability to rebalance internally, titrate exposures, and manage risk deliberately rather than outsourcing those decisions to an index committee whose incentives may not align with yours.

Opinion: target date funds are not wrong, they are incomplete. They are a reasonable base case for people who want simplicity, but they are rarely optimal for anyone who takes their balance sheet seriously. The real future of personal finance is not better glide paths. It is portfolios built around income risk, expense structure, and global diversification, designed to hedge the life you actually live.

Image: Campbell (2025)